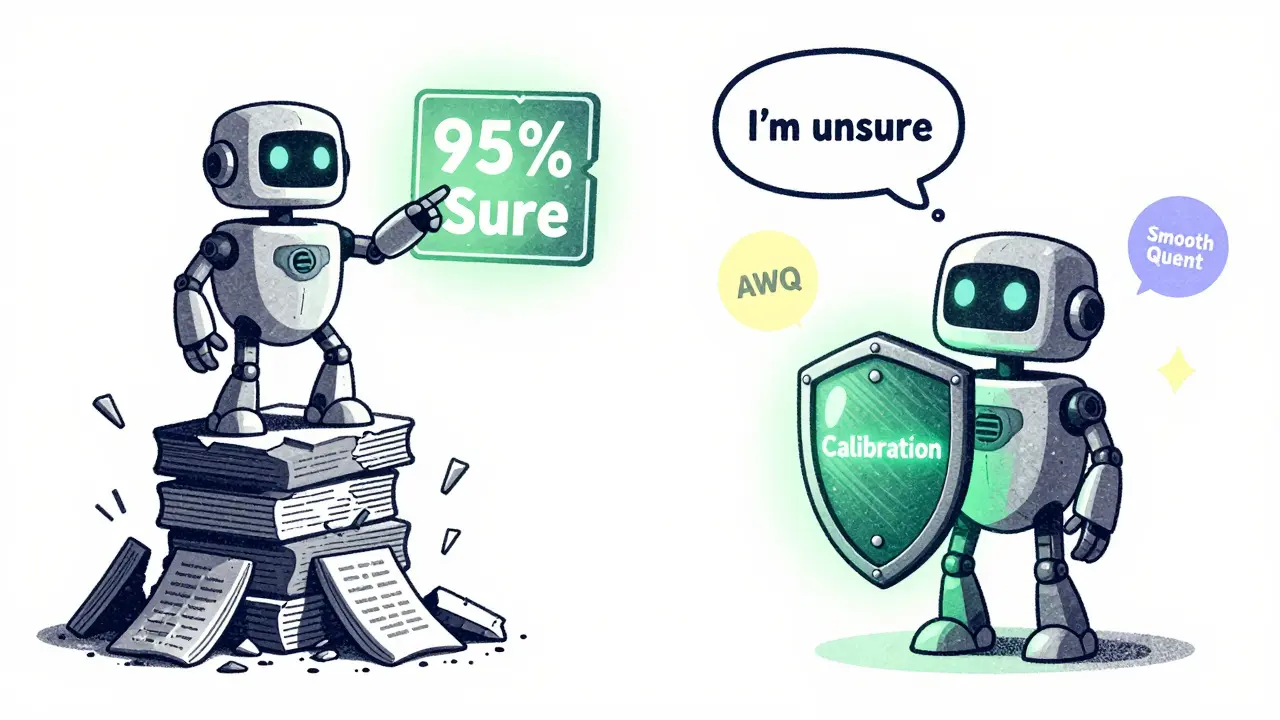

Large language models (LLMs) can sound incredibly smart. They write essays, answer complex questions, and even draft code. But here’s the problem: they don’t always know when they’re wrong. A model might confidently give you a made-up fact, or answer a question it has no business answering. That’s not just annoying-it’s dangerous in real-world applications like healthcare, legal advice, or customer support.

This is where post-training calibration comes in. It’s not about making the model smarter. It’s about teaching it to know when it’s unsure. Calibration adjusts how a model expresses its confidence so that when it says it’s 90% sure, it’s actually right 90% of the time. And when it’s uncertain, it learns to say, "I don’t know."

Why Calibration Matters More Than Accuracy Alone

Many teams focus on accuracy-how often the model gets the right answer. But accuracy without calibration is misleading. Imagine a model that gets 95% of medical diagnosis questions right. Sounds great, right? But if it’s only 60% confident when it’s right, and 95% confident when it’s wrong, you’re in trouble. Users will trust it blindly. And that’s exactly what happens with uncalibrated models.

Calibration fixes this mismatch. It ensures the model’s confidence score matches reality. A 70% confidence rating should mean the model is correct in about 7 out of 10 cases. When this alignment happens, users can make better decisions. They can trust high-confidence answers and double-check or skip low-confidence ones.

Two Ways to Measure Confidence: External and Internal

There are two main ways to calibrate an LLM’s confidence. The first is external: you train a separate neural network to predict whether the LLM’s answer is correct. This helper model looks at the input, the output, and even the internal activations inside the LLM. It doesn’t care what the LLM thinks-it just analyzes patterns to guess accuracy.

The second approach is internal: you ask the LLM itself how confident it is. This is done by adding a simple prompt like, "On a scale of 1 to 10, how sure are you?" or by using the model’s own probability distribution over possible next tokens. The idea is that if the model’s top-choice token has a probability of 0.98, it’s probably confident. But this isn’t always reliable. Sometimes, the model picks a high-probability word even when it’s wrong.

Studies from Carnegie Mellon show that combining both methods works best. The external model catches when the LLM is overconfident, while the internal signal gives a quick, low-cost estimate. Together, they reduce overconfidence by up to 40% in real-world tests.

How Post-Training Changes the Model’s Structure

Most people think fine-tuning just tweaks weights. But recent research using singular value decomposition (SVD) reveals something deeper. After post-training, the model doesn’t just adjust numbers-it rotates and scales its internal geometry.

SVD breaks down the weight matrices in attention layers into three parts: left vectors, singular values, and right vectors. Researchers found that post-training doesn’t randomly change these. Instead, it applies two consistent changes:

- Near-uniform scaling of singular values: This acts like a volume knob. It reduces the influence of less important features, making the model’s attention more focused.

- Orthogonal rotation of singular vectors: This is the real magic. The model rotates its internal representations in a coordinated way across layers. If you break this rotation-even slightly-the model’s performance crashes.

This means post-training isn’t just learning new facts. It’s reorganizing how the model thinks. The pretrained model has a certain "shape" of knowledge. Calibration reshapes it without adding new data. Think of it like tuning a guitar: you’re not changing the strings-you’re adjusting the tension so the notes ring true.

Calibration and Quantization: Making Models Smaller Without Losing Trust

Calibration isn’t just for accuracy. It’s also critical for making models faster and smaller. When you quantize an LLM-converting 32-bit floating-point numbers to 8-bit integers-you lose precision. That can hurt performance.

That’s where calibration steps in. Before quantizing, you run a small dataset (often just 128-512 samples) through the model to measure the range of activations. The most common method, min-max calibration, uses the highest and lowest values seen to set scaling factors. But it’s fragile. One outlier can throw everything off.

Advanced methods like SmoothQuant and AWQ (Activation-aware Weight Quantization) fix this. AWQ, introduced in 2023, looks at how activations behave across different inputs and adjusts weight scaling per channel. It doesn’t just minimize error-it minimizes error where it matters most. In tests, AWQ maintained 98% of the original model’s accuracy after quantization, while min-max dropped to 85%.

For edge devices or low-latency apps, this matters. You can run a 7B model on a phone with near-full performance-if you calibrate it right.

How Calibration Fits Into the Bigger Post-Training Picture

Calibration doesn’t happen in isolation. It’s one piece of a larger post-training pipeline that includes fine-tuning, alignment, and reinforcement learning.

Supervised fine-tuning teaches the model to follow instructions using labeled examples. RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) uses human preferences to train a reward model, then fine-tunes the LLM to maximize that reward. But RLHF is expensive. It needs hundreds of human annotations and complex training loops.

Newer methods like ORPO (Odds Ratio Preference Optimization) simplify this. Instead of training a separate reward model, ORPO uses preference data directly in the loss function. It simultaneously improves task accuracy and alignment with human preferences in one step. In benchmarks, ORPO matched or beat RLHF while using 30% less compute.

Calibration works alongside these methods. A model fine-tuned with ORPO might still be overconfident. Calibration ensures its confidence scores are trustworthy. It’s the final polish.

The Human Side: Confidence Isn’t Just a Number

Here’s the thing: a model can be perfectly calibrated mathematically, but still fail in practice. Why? Because humans don’t interpret numbers the way engineers expect.

Studies in psychology show people either ignore confidence scores or treat them as absolute. A 90% confidence rating might make someone stop thinking altogether. A 60% rating might make them distrust a correct answer.

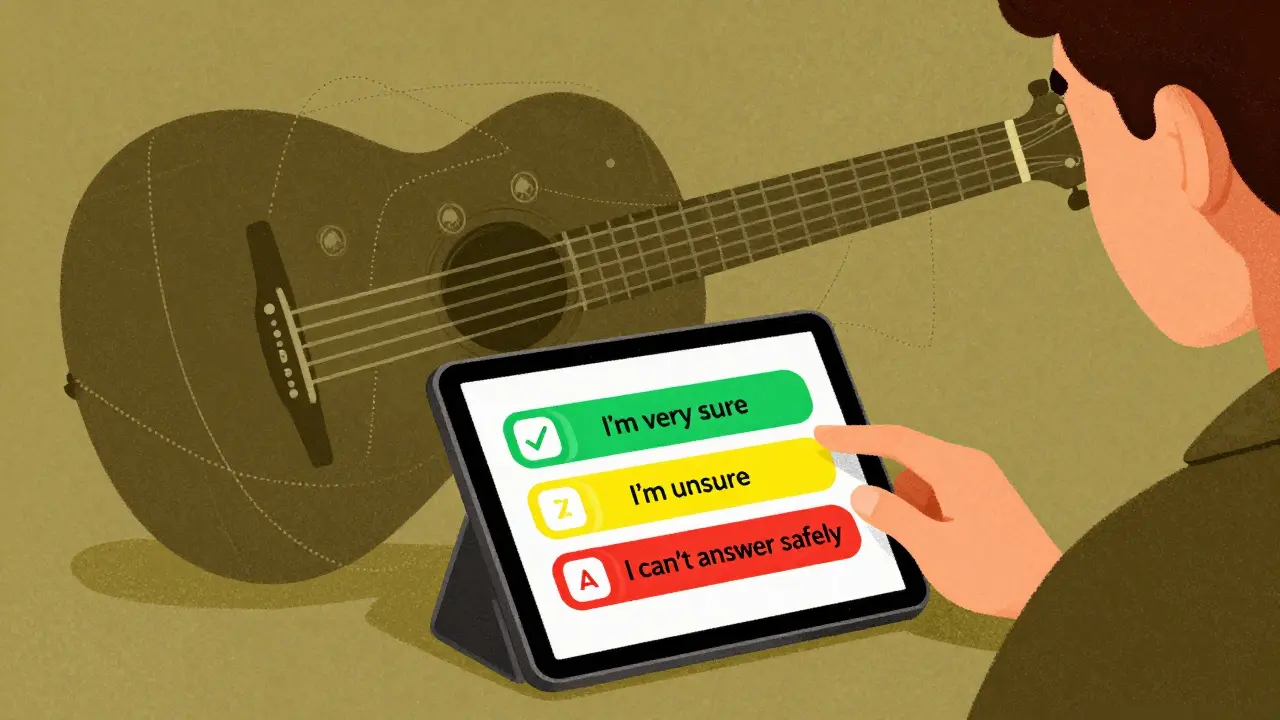

That’s why interface design matters. Instead of showing "92% confidence," better systems say:

- "I’m very sure about this."

- "I’m unsure-here are a few possibilities."

- "I can’t answer this safely."

Some systems even show a "confidence meter" with color coding: green for high, yellow for medium, red for low. Others use natural language explanations: "I’m basing this on sources from 2022, but newer data exists."

This isn’t just UX-it’s safety. Calibration without thoughtful presentation is like giving someone a speedometer without labels.

Challenges and Pitfalls

Calibration isn’t magic. It comes with risks.

- Catastrophic forgetting: If you calibrate on one task, the model might forget how to do others. This is especially true if you use small datasets.

- Reward hacking: A model might learn to output high confidence scores without being right. It’s gaming the system.

- Overfitting calibration: If you calibrate on a dataset that’s too narrow, the model won’t generalize. A medical model calibrated on hospital notes might fail on patient forum questions.

- Latency trade-offs: External confidence models add inference time. For real-time apps, that’s a problem.

The best approach is layered: start with internal confidence, use lightweight calibration on a diverse set of examples, and validate with real user feedback. Don’t try to fix everything at once.

What You Should Do Today

If you’re deploying an LLM, here’s your checklist:

- Test your model’s calibration. Run 100 real-world prompts and compare confidence scores to actual accuracy.

- If confidence and accuracy don’t match, apply a simple temperature adjustment first. Lowering temperature from 0.8 to 0.5 often improves calibration.

- Use AWQ or SmoothQuant if you’re quantizing. Don’t rely on min-max.

- For critical applications, add a confidence filter: reject answers below 75% confidence.

- Present confidence in human-readable terms-not percentages.

You don’t need a PhD to start. Just measure. Just test. Just ask: "When the model says it’s sure, is it right?"

What’s the difference between fine-tuning and calibration?

Fine-tuning changes what the model knows-like teaching it to answer medical questions. Calibration changes how confident it is about what it knows. You can fine-tune a model to be accurate and still have it overconfident. Calibration fixes that mismatch.

Can I calibrate my LLM without extra training?

Yes, in some cases. Temperature scaling-a simple adjustment to the softmax function-can improve calibration with no retraining. You just lower the temperature (e.g., from 1.0 to 0.7) to make high-probability outputs even more dominant. It’s not perfect, but it’s fast and free. For better results, combine it with a small calibration dataset.

Do open-source models need calibration?

Absolutely. Open-source models like Llama 3 or Mistral are often released without calibration. Their confidence scores are unreliable by default. If you’re using them in production, you must calibrate them. Many teams skip this step and wonder why their users lose trust.

How much data do I need to calibrate a model?

You don’t need much. For basic calibration, 100-500 representative prompts are enough. For quantization, 128-512 samples work well. The key isn’t volume-it’s diversity. Use examples from real use cases, not synthetic data.

Is calibration the same as uncertainty estimation?

They’re closely related but not the same. Uncertainty estimation tries to quantify all types of uncertainty-like data gaps or ambiguous questions. Calibration focuses on one thing: whether the model’s confidence matches its actual accuracy. You can have good calibration without full uncertainty estimation, and vice versa.