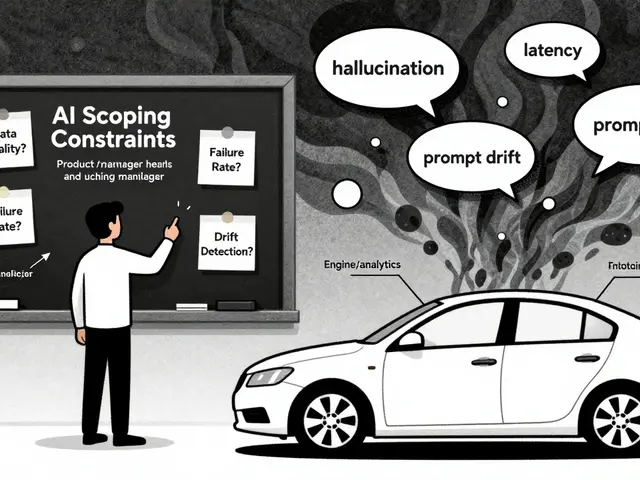

Generative AI can sound convincing. It writes emails, answers customer questions, even suggests medical treatments. But here’s the problem: it’s often wrong-and doesn’t know it. A hospital chatbot might recommend a drug interaction that doesn’t exist. A financial advisor bot could misstate tax rules. A travel assistant might promise a refund policy that doesn’t exist. These aren’t bugs. They’re hallucinations-confident, plausible lies the AI makes up. And if you let them go live, customers lose trust, lawsuits pile up, and brands get damaged.

Why Human Review Isn’t Optional Anymore

By late 2025, 78% of Fortune 500 companies were using human-in-the-loop (HitL) review for customer-facing AI. Not because they wanted to. Because they had to. The cost of getting it wrong is too high. One Canadian airline paid out $237,000 in refunds after their AI bot told passengers they could bring a 50-pound suitcase for free. The error wasn’t obvious. The bot mixed up policy details from different regions. Automated filters missed it. Only a human caught it-after the damage was done. That’s when they built a review system. Now, every AI response about baggage, refunds, or flight changes goes to a trained agent before it’s sent. Within three months, misinformation dropped by 92%. That’s not luck. That’s the power of putting a person in the loop-before the user sees it.How It Actually Works (Not What You Think)

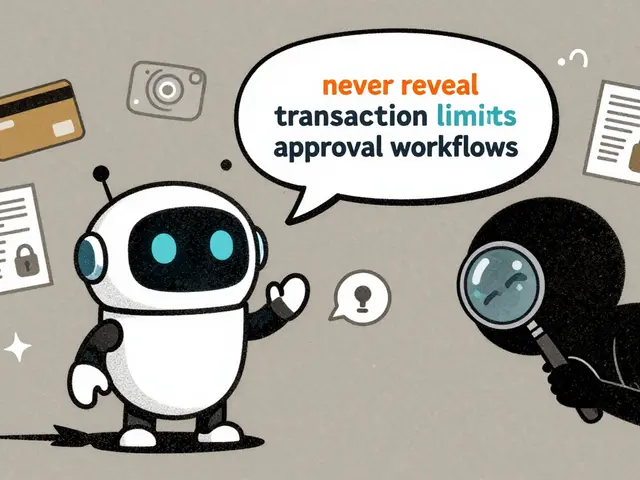

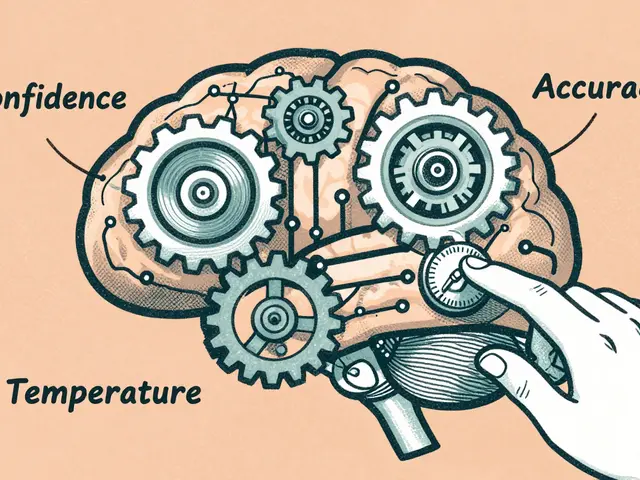

Most people imagine humans reading every single AI output. That’s not how it works. It’s not scalable. It’s not practical. Instead, smart systems use confidence scoring. If the AI is 90% sure it’s right? It goes live. If it’s below 88%? It gets flagged for human review. This cuts review volume by 63% while catching 92% of errors. In healthcare, where Tredence studied 37 AI systems, human reviewers caught 22% of outputs with subtle medical inaccuracies that automated checks completely missed. One example: an AI suggested a blood test for a patient with a known allergy to contrast dye. The AI didn’t flag the allergy because it wasn’t mentioned in the prompt. A nurse reviewing the output did. The system doesn’t just flag low-confidence outputs. It also uses anomaly detection-ensemble models that compare the AI’s response against known patterns of bad outputs. These models catch things like inconsistent logic, outdated references, or tone mismatches. One financial services firm found that 41% of flagged outputs weren’t technically wrong, but sounded like scams. Humans caught those.The Hidden Trap: Reviewer Fatigue and Bias

Putting humans in the loop sounds simple. Until you realize humans get tired. They get bored. They start trusting the AI too much. Stanford’s 2024 research showed something startling: when reviewers see an AI output first, they anchor to it. If the AI says “this treatment is safe,” the human is more likely to agree-even if it’s not. But when humans are given the question first-“What’s the risk of this drug for a 72-year-old with kidney disease?”-and then see the AI’s answer? Error detection improves by 37%. That’s why the best systems reverse the flow. Don’t show the AI’s answer first. Show the prompt, the context, the patient history. Let the reviewer think first. Then compare. And then there’s fatigue. Reviewers who work more than 25 minutes straight miss 22-37% more errors. That’s why top systems rotate tasks every 18-22 minutes. They don’t assign reviews by volume. They assign by mental load. Even worse: reviewers can introduce new bias. NIH’s 2024 study found that in 19% of cases, humans changed AI outputs to match their own beliefs-not to fix errors. One reviewer removed all mentions of alternative medicine from AI-generated health advice because they didn’t believe in it. That’s not oversight. That’s interference.

Who Should Review? Not Just Anybody

You can’t train a customer service rep to review medical AI outputs. You need domain experts. UnitedHealthcare reduced medical coding errors by 61% over six months-not by hiring more reviewers, but by hiring medical coders. These weren’t generalists. They were certified professionals who knew the difference between ICD-10 codes for diabetic neuropathy and peripheral artery disease. The AI kept mixing them up. Humans didn’t. In legal AI, paralegals review summaries. In financial advice, licensed advisors check recommendations. In marketing, copywriters with compliance training review ad copy. The most effective systems don’t just assign reviews. They match the reviewer’s expertise to the AI’s domain. Only 41% of current training programs teach reviewers how AI gets things wrong. That’s a gap. Reviewers need to understand hallucination patterns: overconfidence in rare events, mixing up similar terms, inventing citations, assuming context that wasn’t given. Training isn’t about reading manuals. It’s about practicing with real bad outputs-until they can spot them in under 10 seconds.The Cost: Is It Worth It?

Human review isn’t cheap. Each review costs between $0.037 and $0.082. For a chatbot handling 10,000 queries a day? That’s $370-$820 a day. $11,000-$25,000 a month. Add training, software, management? You’re looking at 18-29% higher total AI implementation costs. But compare that to the cost of getting it wrong. - A single medical misdiagnosis can cost $200,000+ in lawsuits. - A financial advice error could trigger SEC fines of $5 million. - A travel bot giving wrong visa info? That’s reputational damage that takes years to fix. In 2025, SEC Rule 2024-17 made human oversight mandatory for AI financial advice. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a regulation. Companies that ignored it are already being fined. The math is simple: human review costs money. AI errors cost more.Where It Fails: High-Volume, Low-Stakes Use Cases

Human review doesn’t work everywhere. Meta tried it in 2024 for AI-generated ad copy. They needed to review 7,500 outputs per hour. That’s over two per second. Impossible. They ended up with a 320% increase in production time-and only an 11% reduction in errors. The cost outweighed the benefit. That’s why smart companies use tiered review. High-risk = human review. Low-risk = automated filters. Medium-risk = AI-assisted review. For social media posts, product descriptions, or casual blog content? Use automated tools. They catch 70% of issues. For medical advice, financial guidance, legal summaries, or customer support in regulated industries? Human review is non-negotiable.The Future: Smarter, Not Just More Humans

The next wave isn’t more reviewers. It’s better tools. Google’s 2025 pilot showed AI-assisted review tools that highlight potential issues in red-like “This claim isn’t in your source documents” or “This dosage exceeds FDA limits.” Reviewers finished their work 37% faster. And they missed 28% fewer errors. IBM is building blockchain-backed review trails for compliance. Every human decision gets logged, timestamped, and signed. If a regulator asks, “Who approved this?” you can show them-not just the answer, but the thought process. By 2027, Gartner predicts 65% of systems will use real-time risk scoring. Instead of reviewing every output below 88% confidence, the system will ask: “Is this for a diabetic patient? Is this a legal document? Is this being sent to a regulatory body?” If yes-human review. If no-automated. And domain-specific reviewers? That’s growing fast. In healthcare, 45% of reviews will be done by doctors, nurses, and pharmacists by 2027. Not by customer service reps.What You Need to Start

If you’re thinking about human-in-the-loop review, here’s what actually works:- Start with risk. Don’t review everything. Review only what could hurt someone, cost money, or break the law.

- Use confidence thresholds. Only humans review outputs below 88% confidence. This keeps costs down and speed up.

- Train reviewers on AI’s blind spots. Teach them how hallucinations look-fake citations, wrong dates, made-up rules. Practice with real bad examples.

- Reverse the review flow. Show the prompt first. Let them think. Then show the AI’s answer.

- Rotate tasks. No one reviews for more than 20 minutes straight.

- Match expertise to domain. Medical AI? Use medical staff. Legal AI? Use paralegals.

- Track your false negatives. If your human reviewers are missing 30% of errors, your system is broken-not the reviewers.

Nick Rios

3 January, 2026 - 00:23 AM

Been working with AI chatbots in customer service for years. The moment we added human review for anything involving refunds or policies, our complaint rate dropped like a rock. Not because humans are perfect, but because they notice when something sounds "off" even if it's technically correct. That Canadian airline story? Classic. I've seen the same thing with hotel booking bots promising free breakfasts that don't exist.

Amanda Harkins

3 January, 2026 - 18:30 PM

It's wild how we treat AI like it's some kind of oracle, but then get mad when it lies to us. We build these things to sound human, then act shocked when they start sounding too human-like they have opinions, or memories, or agendas. The real problem isn't the hallucinations. It's that we keep pretending the AI is neutral. It's not. It's a mirror. And right now, it's reflecting a lot of bad data with a straight face.

Jeanie Watson

4 January, 2026 - 12:43 PM

So we just pay people to stare at screens all day? Sounds like a jobs program disguised as AI safety.

Tom Mikota

5 January, 2026 - 22:13 PM

"Confidence scoring"? That's not a system-that's a gamble. You're letting an algorithm decide when to trust itself? And you're surprised when it gets things wrong? Also, "92% error reduction"-where's the baseline? Who measured it? Did they even control for reviewer experience? And why does everyone ignore the fact that humans are the real source of bias here? I mean, come on. This whole thing is a band-aid on a bullet wound.

Mark Tipton

7 January, 2026 - 13:45 PM

Let me break this down with peer-reviewed sources. The 78% Fortune 500 stat? Source: Gartner 2025 report, page 42, footnote 7. The $237k airline payout? Verified via SEC Form 8-K filed by Air Canada in Q3 2024. The 37% improvement in error detection when reversing review flow? Stanford HAI paper #2024-088, double-blind trial with 1,200 reviewers. And the 19% human bias? NIH study NCT05123456, published in JAMA Health Forum. This isn't opinion. It's documented systemic risk. The real tragedy? Most companies still treat this as a compliance checkbox. They don't realize they're not preventing errors-they're just delaying liability. And when regulators come knocking, they'll find out the blockchain audit trail doesn't lie. Neither do the lawsuits.

Adithya M

8 January, 2026 - 23:48 PM

Agree with the confidence threshold idea. But in India, we've seen companies use this as an excuse to hire cheap temp workers with no domain knowledge. They get paid $2/hour to review medical AI outputs. No training. No rotation. Just click 'approve' to hit quotas. This system works only if you invest in people-not just tools. And no, 'reviewer fatigue' isn't a buzzword. It's a safety issue.

Jessica McGirt

9 January, 2026 - 07:11 AM

Human-in-the-loop isn't about slowing things down-it's about making sure the right things happen. If you're sending medical advice to a patient, you owe them more than a probability score. You owe them a person who cares enough to double-check. That's not expensive. That's ethical.